Making an iPhone Switch Control without Images

September 16, 2010

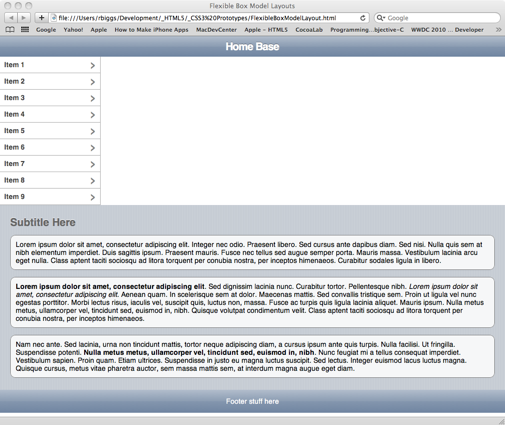

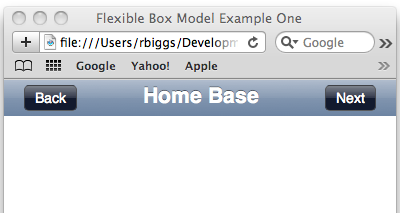

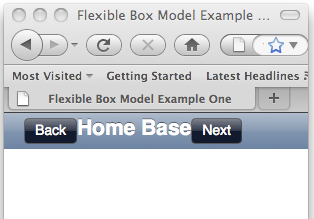

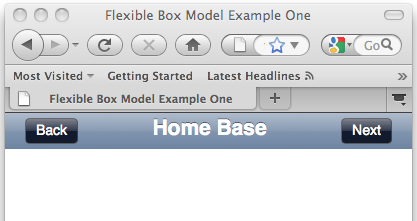

Works on desktop Safari, Chrome and Firefox, iPhone, iPod Touch and iPad.

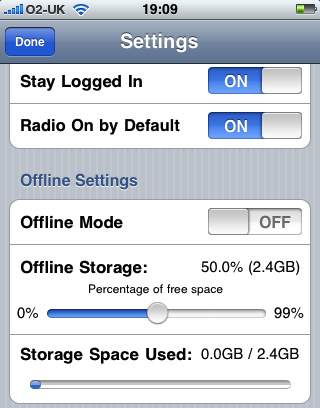

On the iPhone and iPad, Apple uses a control called switch. It’s actually a different take on the checkbox. Like radio buttons, checkboxes do not lend themselves to touch interfaces, especially guys with fat fingers, cough! Instead of making us suffer with those dinky checkboxes, Apple uses a more visual cue to what the user is actually doing, switching something on or off. As a matter of fact, that’s exactly how the control is labeled: “on” or “off”. They’re really easy to use, just swipe your finger to throw the switch, done. In case you’re not sure what I’m talking about, here they are:

OK, so all the mobile Web frameworks have a switch control. And I hate them all. They either do an instant switch between the on and off state, using an image sprite, or they do this really lame thing where they animate the horizontal background position of the image on a checkbox with its default styles removed. None of those implementations feels the same as when you swipe the switch control in a native iOS app.

So what am I going to do? I tell you, I’m going to throw the friggin’ image out and build the whole control from scratch using just HTML, CSS3 and some JavaScript to make it work. Bada-bing! To start with, here’s the basic markup for a checkbox:

<div class="checkbox unchecked" id="sleepSwitch"> <div class="on">ON</div> <div class="thumb"><span></span></div> <div class="off">OFF</div> <input type="checkbox" value="ZZZZZZZZ!" offvalue="But, I need more sleep!"> </div>

As we did when we created iPhone style radios buttons, we’re using real checkboxes in our iPhone switch controls. And like in the radio button example, we’ll set the checkbox input’s display value to “none”. We’ll use CSS3 properties to style the markup to look like a real iOS switch control and we’ll attach event listeners to set the input checkbox’s check state to true or false, depending on whether we want it to be selected or not.

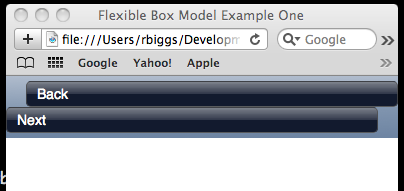

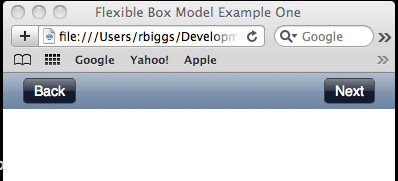

To create this switch control we’ll need to style the frame named “checkbox” with rounded corners. Notice that the markup above contains three parts: the on state, the thumb and the off state. The rounded frame will only be wide enough to show one state plus the thumb. Using CSS3 transitions and transforms, a click or touch will cause the three elements to side back and forth within the rounded frame. For positioning the switch’s elements and sliding them back and forth we’re going to use CSS3 3d transforms on the x axis. Here is the CSS to make this happen:

/* Checkbox */

.checkbox {

display: -webkit-box;

-webkit-box-orient: horizontal;

-webkit-box-pack:justify;

-webkit-box-sizing: border-box;

-webkit-tap-highlight-color: transparent;

width: 94px;

overflow: hidden;

-webkit-border-radius: 6px;

text-align: center;

line-height: 28px;

cursor: pointer;

-webkit-user-select: none;

position: absolute;

right: 10px;

top: 7px;

}

.checkbox > input[type="checkbox"] {

display: none;

}

.checkbox .thumb {

-webkit-border-radius: 7px;

position: relative;

z-index: 3;

border: solid 1px #919191;

-webkit-transition: all 0.125s ease-in-out;

-webkit-transform: translate3d(0px,0%,0%);

}

.checkbox .thumb span {

display: block;

-webkit-box-sizing: border-box;

height: 25px;

width: 38px;

border-top: solid 1px #efefef;

-webkit-border-radius: 6px;

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom, from(#cecece), to(#fbfbfb));

border-top: solid 1px #efefef;

position:relative;

}

.checkbox .on {

color: #fff;

background-image:

-webkit-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom,

from(#295ab2),

to(#76adfc));

width: 54px;

padding-right: 4px;

border: solid 1px #093889;

-webkit-border-top-left-radius: 6px;

-webkit-border-bottom-left-radius: 6px;

margin-right: -6px;

height: 25px;

-webkit-transition: all 0.125s ease-in-out;

position: relative;

-webkit-transform: translate3d(0px,0%,0%);

}

.checkbox .off {

color: #666;

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom, from(#b5b5b5), color-stop(0.50, #fff));

width: 54px;

padding-left: 4px;

border: solid 1px #a1a1a1;

-webkit-border-top-right-radius: 6px;

-webkit-border-bottom-right-radius: 6px;

margin-left: -6px;

height: 25px;

-webkit-transition: all 0.125s ease-in-out;

position: relative;

-webkit-transform: translate3d(-54px,0%,0%);

}

.checkbox.unchecked .thumb {

-webkit-transform: translate3d(-54px,0%,0%);

}

.checkbox.checked .thumb {

-webkit-transform: translate3d(0px,0%,0%);

}

.checkbox.unchecked .on {

-webkit-transform: translate3d(-60px,0%,0%);

}

.checkbox.checked .on {

-webkit-transform: translate3d(0px,0%,0%);

}

.checkbox.unchecked .off {

-webkit-transform: translate3d(-54px,0%,0%);

}

.checkbox.checked .off {

-webkit-transform: translate3d(6px,0%,0%);

}

/* For Very Important changes, use the orange checkbox */

.checkboxBase.important .on {

border: solid 1px #d87100;

background-image: -webkit-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom, from(#e75f00), color-stop(.5, #ff9c12));

}

/* End Checkbox */

To make the switch more realistic, I’m transforming all three pieces of the switch at the same time. This gives the switch a more realistic feeling. Notice the comment in at the end of the above CSS about the important class. You can use this to indicate a switch that makes a very important change. This class changes the default switch’s blue color to bright orange. This is the color Apple uses to show that a switch’s action is very important.

Having the CSS defined for the look and animation brings us close to the finished control, but we need to write some JavaScript to make the switch interactive. The JavaScript needs to do two things: toggle the classes “checked” and “unchecked” on the switch, and toggle the checked value of the checkbox between true and false. I’m using the ChocolateChip JavaScript framework to do this. You can switch my code to whatever library you want. If you know basic JavaScript, it shouldn’t be hard. Here’s the JavaScript to make it happen:

Element.prototype.toggleSwitch = function() {

if (this.hasClass("switch")) {

if (this.last().checked === true) {

this.last().checked = false;

this.toggleClass("checked", "unchecked");

} else {

this.last().checked = true;

this.toggleClass("checked", "unchecked");

}

} else {

return false;

}

};

The last() used in the code above is a ChocolateChip method to return the last child of the control, which happens to be the checkbox input. That way we can set its checked state to true or false.

Now that we have the code to setup up the switch control, we can make it work as follows:

$(".switch").forEach(function(checkbox) {

checkbox.bind("click", function() {

this.toggleSwitch();

});

checkbox.bind("touchstart", function(e) {

e.preventDefault();

this.toggleSwitch();

});

});

That’s it to make the switch switchable. But to make it do something you’d need a bit more as well. In my example, I’m getting some values from the switch and outputting it to a response field like this:

$(".switch").forEach(function(checkbox) {

checkbox.bind("click", function() {

if (this.last().checked === true) {

$("#switchResponse").fill(

this.last().getAttribute("value"));

} else {

$("#switchResponse").fill(

this.last().getAttribute("offvalue"));

}

});

checkbox.bind("touchstart", function(e) {

if (this.last().checked === true) {

$("#switchResponse").fill(

this.last().getAttribute("value"));

} else {

$("#switchResponse").fill(

this.last().getAttribute("offvalue"));

}

});

});

You can try this out online or download the source code.

You must be logged in to post a comment.