CSS Gradients for IE9

October 29, 2010

This works with Desktop IE9, Desktop Firefox, Desktop Chrome, Desktop Safari, Desktop Opera, iOS, and Android.

Attention! IE9 will not destroy the world, kill babies, or take away your home or job.

Simply put, IE9 is the best browser Microsoft has ever released. Has it caught up to Chrome, Firefox and Safari? No. But that doesn’t matter. It’s still light years ahead of any other version of IE. All of us should be praying every day for IE users to upgrade to it as soon as possible.

Shortly after the initial launch of the beta of IE9, I began testing to see what kind of support it had for all the rich and exciting features CSS3 offers for Web layout and interaction. The earlier beta’s didn’t have much, but with each release it has gotten better. If you’re already using advanced CSS3 for Web development and never bothered supporting IE before, you’ll want to know what it supports and what it doesn’t. Here’s what it supports at present right from the horse’s mouth. In particular, it supports real CSS opacity, multiple background images, box shadows, border radius, background-clip, background-size, background-position, WOFF for Web fonts, RGBA and HSLA color, box sizing, as well as the full suite of CSS3 selectors. The above post also talks about support for CSS3 2d transforms, however, even with the -ms- vender prefix I am unable to get it to work with the present beta (7).

Update: Transforms are working in Platform Preview 6, which is different from the present public beta. Microsoft is taking a two track approach to releasing this: the public beta for general users to test and a platform preview where features are introduced but not necessary finalized.

So what didn’t make it into IE9? First up, the flexible box model. Once you’ve used the flexible box model for layout, it’s as painful as eating glass to go back to using floats and positioning for layout. No text shadow, which is a strange omission considering they have box shadow. No border images. No CSS transitions. The single-threaded nature of JavaScript makes it inefficient for complex animations. Offloading style animations to the browser’s CSS rendering engine frees up JavaScript and allows the browser to use threads and hardware acceleration for better optimization. In my opinion, CSS3 transitions are more important than CSS3 transforms. Since Firefox, Opera and Webkit all support CSS3 transitions to some degree, it’s a odd omission for IE9. No 2d or 3d transforms. As I mentioned before, transforms do not appear to be implemented in the current beta. (Someone correct me if I’m wrong on this.) The thing I love about CSS3 transitions and transforms is that they allow you to create user interactions that make a Web application feel like a native one, blurring the difference between desktop and Web. No CSS3 keyframe animation. If you thought CSS3 transitions were awesome, you be blown away by CSS keyframe animations.

When I look at IE9’s support for CSS3, it appears they decided to pick the low hanging fruit: border radius, drop shadow, multiple backgrounds, etc. But the flexible box model, gradients, transitions, transforms and keyframe animation are the things in CSS3 that really turn your head.

I have no experience working with Adobe Flash. I do have extensive experience working with Microsoft’s Silverlight platform. I love how it enables you to create rich, interactive user interfaces where you can customize every aspect of a control’s look and feel. Chrome, Firefox and Safari’s support for CSS3 enables a similar high level of possibilities for the creation of Web user interfaces. IE9 is attempting to achieve feature parity with the other browsers and is making good progress. But if you want to use the CSS3 features that IE9 doesn’t support, you’ll need to find workarounds.

Presently my main area of focus is the mobile Web on Android, Blackberry 6, iOS and WebOS. That’s a world ruled by Webkit. But I usually make efforts to ensure that my solutions can also work with modern desktop browsers: Chrome, Firefox and Safari. That involves a lot of vender prefixes: -moz, -webkit. And then you need to future proof it by supplying the same property without the vendor prefix. This technique allows browsers that understand the properties, like IE9, to also render them without any extra effort.

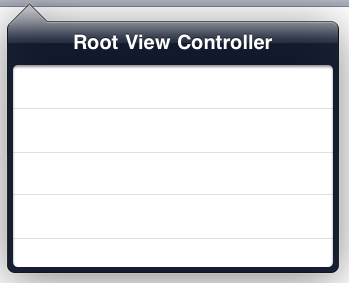

I’m going to take one example of an HTML/CSS3 implementation of iOS’s popup dialog box which I originally created for use on iOS devices and show how I got it to render equally in Chrome, Firefox, IE9, Opera and Safari. At the end of this post you’ll find links to try it out online or download it. One thing, I’m not using any image pieces, just CSS3 properties. Here’s the initial state of the page with the popup in Safari and Firefox:

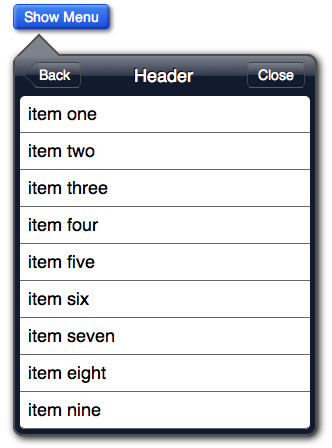

Here’s the page with the popup in view in Safari and Firefox:

Here’s the same markup in IE9. Notice how it understands border radius, box shadow and RGBA background color, but cannot render the flexible box model layout nor the CSS3 gradients.

IE9’s lack of support for the flexible box model can be resolved by using old-school layout techniques (floats/positioning). But there is no way to fake CSS3 gradients with pngs. When you stretch them they exhibit banding. Since I make extensive use of CSS3 gradients all the time, I felt pressed to find a solution for IE9. After spending some time experimenting with SVG in IE9, I hit on an idea. Using an IE9 specific stylesheet, I would try setting SVG gradients as background images on the element’s that use CSS3 gradients. The technique works quite well. Here’s IE9 with its custom CSS:

First, here’s a CSS3 gradient used by Chrome, Firefox and Safari:

header {

width: 100%;

display: -webkit-box;

display: -moz-box;

display: box;

-webkit-box-orient: horizontal;

-webkit-box-pack:justify;

-webkit-box-align: center;

-webkit-box-sizing: border-box;

-moz-box-orient: horizontal;

-moz-box-align: center;

-moz-box-pack:justify;

-moz-box-sizing: border-box;

box-orient: horizontal;

box-align: center;

box-pack:justify;

box-sizing: border-box;

height: 45px;

margin: 0;

padding: 0 10px;

background-image:

-webkit-gradient(linear, left top, left bottom,

from(#b2bbca),

color-stop(0.25, #a7b0c3),

color-stop(0.5, #909cb3),

color-stop(0.5, #8593ac),

color-stop(0.75, #7c8ba5),

to(#73839f));

background-image:

-moz-linear-gradient(top,

#b2bbca,

#a7b0c3 25%,

#909cb3 50%,

#8593ac 50%,

#7c8ba5 75%,

#73839f);

border-top: 1px solid #cdd5df;

border-bottom: 1px solid #2d3642;

}

As you can see in the above code, we’re defining background images as gradients with a number of color stops. That all a CSS3 background gradient is. As a matter of fact, it’s rendered by the browser as a canvas background image. Since IE9 supports SVG, including as background images, I’ve come up with a way to use SVG gradient images as background gradients. Because SVG is vector-based, the gradients scale without banding. SVG is an XML markup language for describing vector graphics. The HTML5 parsing engine allows SVG to be directly embedded in HTML. But I want background images. By defining the height of the SVG document as 100%, I have an image that will scale to whatever the element is, just like the CSS3 gradient. Here’s the markup that I used to create the gradient for the header. Notice that the SVG gradient has color-stops and offsets like the CSS gradients. They aren’t that different.

<?xml version="1.0" ?>

<svg xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg" preserveAspectRatio="none" version="1.0" width="100%"

height="100%"

xmlns:xlink="http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink">

<defs>

<linearGradient id="myLinearGradient1"

x1="0%" y1="0%"

x2="0%" y2="100%"

spreadMethod="pad">

<stop offset="0%" stop-color="#b2bbca" stop-opacity="1"/>

<stop offset="50%" stop-color="#909cb3" stop-opacity="1"/>

<stop offset="50%" stop-color="#8593ac" stop-opacity="1"/>

<stop offset="100%" stop-color="#73839f" stop-opacity="1"/>

</linearGradient>

</defs>

<rect width="100%" height="100%"

style="fill:url(#myLinearGradient1);" />

</svg>

The document has a height and width of 100%, the gradient is set to expand to 100% and the rectangle is defined with a height and width of 100%. It is possible to turn this SVG image into a datauri and put it directly in the CSS, using use any of the many resources available for datauri conversion. However, the SVG files are just simple text files. If you convert them to datauris, you will not be able to make any changes to them. While putting this demo together I had to constantly tweak the values in the SVG gradients to get them exact. Keeping the SVG files allows you to go back and modify the gradients at any time. Here’s how you use this for IE9:

header {

background-image: url("svg-gradient.svg");

}

That’s it. IE9 will display the above SVG graphic in a manner indistinguishable from native CSS3 gradients.

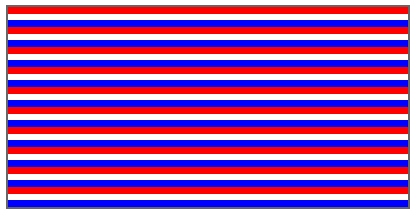

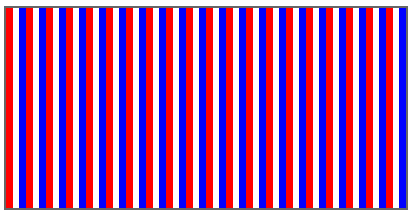

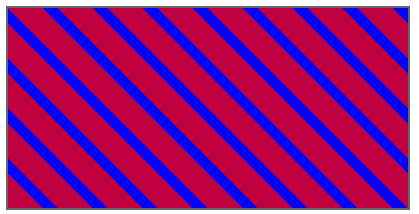

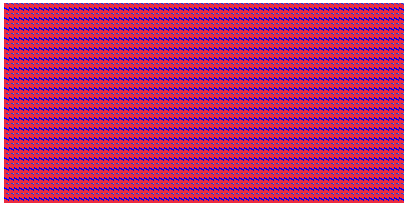

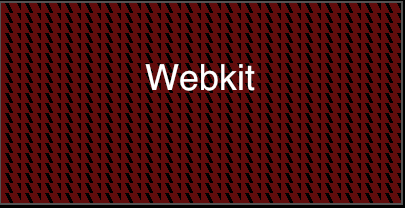

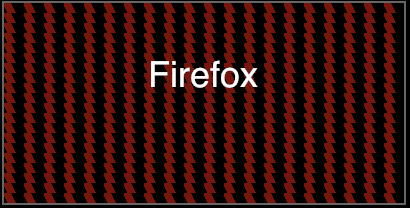

For the repeating striped background gradient on the body tag, I’m using a CSS3 gradient with background sizing and letting it repeat across the page. For IE9 I do the same thing, using background sizing on the SVG equivalent to get the same effect.

Like IE9, Opera also does not support the flexible box model nor CSS3 gradients. Notice how Opera renders the demo basically the same as IE9:

After creating the SVG workaround for IE9 to mimic CSS3 gradients, I started thinking about Opera’s lack of support for CSS3 gradients. Opera has the best support for SVG out of all the browsers. I therefore tried giving Opera the same CSS that I gave IE9. It worked as well as it did for IE9. You can see the results below:

There is very minimal browser sniffing required to make this work across modern browsers. One stylesheet for Chrome, Firefox and Safari, a conditional comment for IE9 and a browser agent sniff for Opera:

<!--[if IE 9]>

<link rel="stylesheet" type="text/css" href="popup-svg.css">

<![endif]-->

<script type="text/javascript">

var Opera = /opera/i.test(navigator.userAgent);

if (Opera) {

var link = document.createElement("link");

link.setAttribute("rel", "stylesheet");

link.setAttribute("href", "popup-svg.css");

document.getElementsByTagName("head")[0].appendChild(link);

}

</script>

Please Note: If you’re going to use this technique in a production environment you should use feature detection because at some point Opera will support CSS gradients. There are a number of ways to accomplish feature detection. Perhaps the easiest is to use Modernizr.

You can try out this demo online or download the source code. Feel free to use the included SVG files as templates for your own gradients.

Oh, and one last thing. I’m using the ChocolateChip mobile JavaScript framework for this demo. Originally I created it to work on mobile devices using Webkit browsers. I therefore provided no support for the JScript quirks of IE. But since IE9 has a completely rewritten JavaScript engine and uses the standard event model and DOM interfaces like the other browsers, ChocolateChip works fine on it without modification. That definitely put a smile on my face.

You must be logged in to post a comment.