The Holy Grail of Mobile Layout

January 30, 2011

The Holy Grail of Mobile Layout

The perfect mobile layout should allow the presence of a navbar, a content area and maybe a footer toolbar. This layout should resize with orientation changes such that the bottom toolbar is always at the bottom and the content area resizes its width and height to fit the new dimensions. This is tough because, first off, there is not fixed positioning, and secondly, there is no single finger scrolling in Webkit for CSS defined scrolling regions.

it’s taken me a while to come up with a solution to these layout requirements. Any of you trying to make a Web app feel like a native mobile app know the frustration of trying to deal with orientation change and complex layout. Not being able to make a toxic mix of viewport meta tags, CSS media queries and onorientationchange events work to give me a fluidly resizing layout when the mobile device’s orientation changed drove me to despair. I compensated early on using JavaScript to resize everything, except I had to pay a performance penalty, especially if an app was complex. After a lot of sweat and blood and endless trial and error, I finally came up with a CSS only solution to making a layout that resizes smoothly with orientation changes.

So, the first big mistake, one that everyone and their brother recommends, is not to use the meta tag viewport settings of device width and device height. Instead, just use the initial scale, maximum scale and user scalability:

<meta name="viewport" content="initial-scale=1.0, maximum-scale=1.0, user-scalable=no">

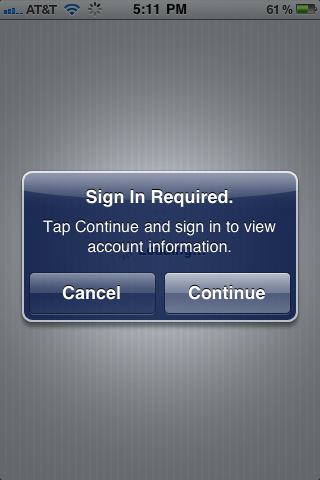

The reason is that no matter what you set the width and height to with CSS, Webkit insists on thinking the document should have the height and width from when the document first loaded. This happens even if you use a CSS value of “width: 100%”. Switching from portrait to landscape, you’ll see that your layout fails to fill the width of the landscape screen:

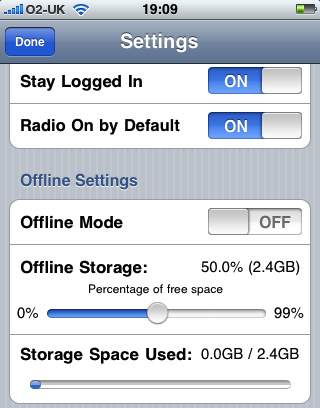

As you can see with the landscape orientation the layout fails to fill the available width of the device. This app has its root elements’ widths set to 100% and a meta tag of:

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width; height=device-height; initial-scale=1.0, maximum-scale=1.0, user-scalable=no">

Removing the device width and height from the meta tag will give us the fluid layout we seek:

<meta name="viewport" content="initial-scale=1.0, maximum-scale=1.0, user-scalable=no">

With the above change, when switching this document loaded in portrait orientation to landscape mode orientation we get a resized document the way we would like:

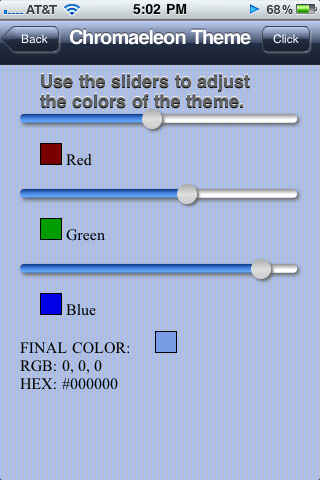

OK, so we have a navbar on the top, but what if we want a toolbar on the bottom? No problem. We can accomplish that with a few adjustments. To fix the toolbar to the bottom we’ll use absolute positioning. One thing to remember about this layout technique, if you are going to have navbars or toolbars, you’ll need to adjust the height of the content so that it fits the space left over by the bars. I do this using a class or class on the content section. A navbar or toolbar has a default height of 45 pixels, so you’d want to position your content that distance from a navbar or toolbar. To make this work, we’re going to have to use absolute positioning on the content section and on any bottom toolbar. One thing rather frustrating about using absolute positioning on block elements is that it causes them to collapse to what their content is, even with they have a width of 100%. We can get around this by setting the appropriate side to 0 pixels. For a bottom toolbar this could be something like this:

.toolbar.bottom {

height: 45px;

position: absolute;

bottom: 0;

left: 0;

right: 0;

}

With the above measurement, we have a toolbar that is 45px high fixed to the bottom and stretching from side to side. This toolbar will maintain these dimensions and placement even with an orientation change. We’ll need to do something similar for the content area. Like I said, we’ll need to use absolute positioning and account for any space taken up by a nav or toolbar. I use classes to do this, such as “withNavbar”, or “withNavbar withBottomToolbar”, or “withBottomToolbar”. The CSS for these classes would be something like this:

/* Definition for content area that fills the screen: */

#content {

position: absolute;

top: 0;

right: 0;

bottom: 0;

left: 0;

}

#content.withNavbar {

top: 45px;

right: 0;

bottom: 0;

left: 0;

}

#content.withBottomToolbar {

top: 0;

right: 0;

bottom: 45px;

left: 0;

}

#content.withNavbar.withBottomToolbar {

top: 45px;

right: 0;

bottom: 45px;

left: 0;

}

We also need to make sure that the document’s content doesn’t bleed down below the bottom toolbar. We do this by wrapping the entire document in a div. I give it an id of #main:

<body> <div id="main"> <div class="navbar"> <h1>The Title</h1> </div> <div id="content" class="withNavbar withBottomToolbar"> <ul class="table-view"> <li><span class="title">Item One</span></li> <li><span class="title">Item Two</span></li> <li><span class="title">Item Three</span></li> <li><span class="title">Item Four</span></li> <li><span class="title">Item Five</span></li> <li><span class="title">Item Six</span></li> <li><span class="title">Item Seven</span></li> <li><span class="title">Item Eight</span></li> </ul> </div> <div class="toolbar placement-bottom"> <div class="button">Edit</div> <div class="button">Save</div> </div> </div> </body>

The styles for the div#main would be:

#main {

width: 100%;

display: -webkit-box;

margin: 0 0 0 0;

padding: 0;

height: 100%;

-webkit-box-orient: vertical;

-webkit-box-align: stretch;

-webkit-box-sizing: border-box;

-webkit-transition: all 0.25s ease-in-out;

overflow: hidden;

position: absolute;

top: 0;

left: 0;

bottom: 0;

right: 0;

}

Although the above arrangement solves the layout problems for mobile interfaces with automatic adjustment with orientation changes, it presents a new problem. That’s the problem of making the data in the content area reachable by the user. You’ll need to add a way for the user to scroll just that area. Normally the whole document would scroll with the browser, with the result that the top part would scroll out of view. Since we’ve fixed the toolbar to the bottom and have the height of the content area control by absolute position affecting its top, right, bottom and left, we need to provide a way to enable scrolling. Actually we could do this very simply using the CSS overflow property: #content { overflow-y: auto; }. However, on mobile Webkit this requires a two finger gesture. Most users would not expect this. They’ll use a single finger and think that the content is not scrollable.

There’s a simple way to provide single finger scrolling with a JavaScript module called “iScroll” created by Matteo Spinelli. This is a great implementation which provides deceleration animation of the scrolling, just like iOS, Android and other mobile OSes. One thing to be aware of when using iScroll, you don’t use it directly on the content container as this would cause that contain to slide up and down over the navbar and toolbar. Instead you’ll need to add an extra div tag inside it and use iScroll on that. iScroll will then enable scrolling of the div inside the content div. There are a number of options, my favorite is for desktop simulation. Here how you would do it:

<div id="content" class="withNavbar withBottomToolbar">

<div id="scrollwrapper">

<!-- Content In Here -->

</div>

</div>

.........

<script type="text/javascript">

var scroller = new iScroll(’scrollwrapper’, { desktopCompatibility :

true });

</script>

This gives you a basic mobile Web interface with a top navbar, a bottom toolbar and a content area with scroll that resizes quickly with orientation change.

Since publishing this article, I’ve created a framework for creating mobile Web apps. It uses many of the techniques explored in my blog posts. You can learn more about the framework by visiting ChocolateChip-UI.com. There are demos you can try in your desktop browser or on your mobile device.

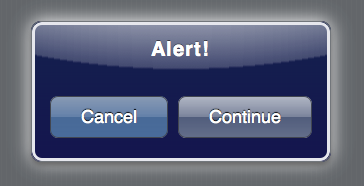

You must be logged in to post a comment.